The study of physics is the study of the universe—and more specifically, just how the hell the universe works. It is without a doubt the most interesting branch of science, because the universe, as it turns out, is a whole lot more complicated than it looks on the surface (and it looks pretty complicated already). The world works in some really weird ways, and though you may need a PhD to understand why, you only need a sense of awe to appreciate how. Here are ten of the most amazing things physicists have discovered about our universe:

10

Time Stops at the Speed of Light

According to Einstein’s Theory of Special Relativity, the speed of light can never change—it’s always stuck at approximately 300,000,000 meters/second, no matter who’s observing it. This in itself is incredible enough, given that nothing can move faster than light, but it’s still very theoretical. The really cool part of Special Relativity is an idea called time dilation, which states that the faster you go, the slower time passes for you relative to your surroundings. Seriously—if you go take a ride in your car for an hour, you will have aged ever-so-slightly less than if you had just sat at home on the computer. The extra nanoseconds you get out of it might not be worth the price of gas, but hey, it’s an option.

Of course, time can only slow down so much, and the formula works out so that if you’re moving at the speed of light, time isn’t moving at all. Now, before you go out and try some get-immortal-quick scheme, just note that moving at the speed of light isn’t actually possible, unless you happen to be made of light. Technically speaking, moving that fast would require an infinite amount of energy (and I for one don’t have that kind of juice just lying around).

Alright, so we just finished agreeing that nothing can move faster than the speed of light—right? Well… yes and no. While that’s technically still true, at least in theory, it turns out that there’s a loophole to be found in the mind-blowing branch of physics known as quantum mechanics.

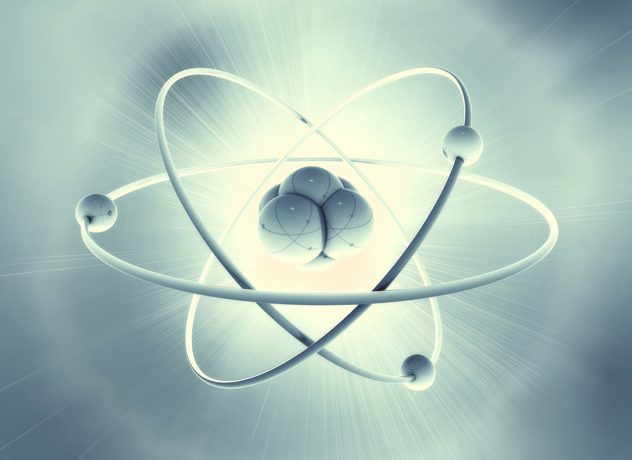

Quantum mechanics, in essence, is the study of physics at a microscopic scale, such as the behavior of subatomic particles. These types of particles are impossibly small, but very important, as they form the building blocks for everything in the universe. I’ll leave the technical details aside for now (it gets pretty complicated), but you can picture them as tiny, spinning, electrically-charged marbles. Okay, maybe that’s kind of complicated too. Just roll with it (pun intended).

So say we have two electrons (a subatomic particle with a negative charge). Quantum entanglement is a special process that involves pairing up these particles in such a way that they become identical (marbles with the same spin and charge). When this happens, things get weird—because from now on, these electrons stay identical. This means that if you change one of them—say, spin it in the other direction—its twin reacts in exactly the same way. Instantly. No matter where it is. Without you even touching it. The implications of this process are huge—it means that information (in this case, the direction of spin) can essentially be teleported anywhere in the universe.

8

Light is Affected by Gravity

But let’s get back to light for a minute, and talk about the Theory of General Relativity this time (also by Einstein). This one involves an idea called light deflection, which is exactly what it sounds like—the path of a beam of light is not entirely straight.

Strange as that sounds, it’s been proved repeatedly (Einstein even got a parade thrown in his honor for properly predicting it). What it means is that, even though light doesn’t have any mass, its path is affected by things that do—such as the sun. So if a beam of light from, say, a far off star passes close enough to the sun, it will actually bend slightly around it. The effect on an observer—such as us—is that we see the star in a different spot of sky than it’s actually located (much like fish in a lake are never in the spot they appear to be). Remember that the next time you look up at the stars—it could all just be a trick of the light.

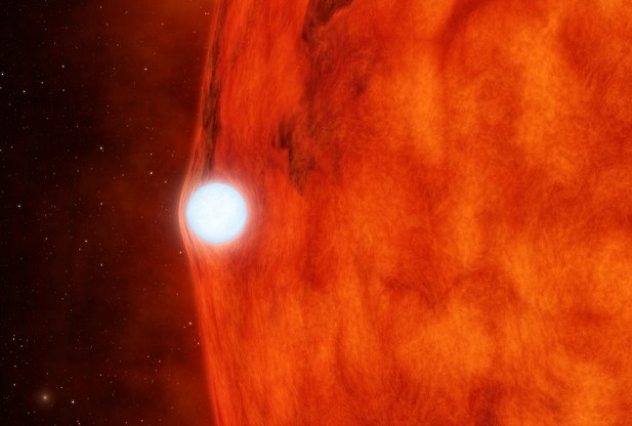

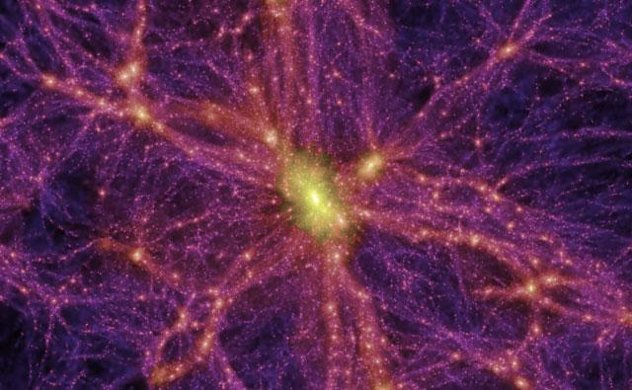

Thanks to some of the theories we’ve already discussed (plus a whole lot we haven’t), physicists have some pretty accurate ways of measuring the total mass present in the universe. They also have some pretty accurate ways of measuring the total mass we can observe, and here’s the twist—the two numbers don’t match up.

In fact, the amount of total mass in the universe is vastly greater than the total mass we can actually account for. Physicists were forced to come up with an explanation for this, and the leading theory right now involves dark matter—a mysterious substance that emits no light and accounts for approximately 95% of the mass in the universe. While it hasn’t been formally proved to exist (because we can’t see it), dark matter is supported by a ton of evidence, and has to exist in some form or another in order to explain the universe.

6

Our Universe is Rapidly Expanding

Here’s where things get a little trippy, and to understand why, we have to go back to the Big Bang Theory. Before it was a TV show, the Big Bang Theory was an important explanation for the origin of our universe. In the most simple analogy possible, it worked kind of like this: the universe started as an explosion. Debris (planets, stars, etc) was flung around in all directions, driven by the enormous energy of the blast. Because all of this debris is so heavy, and thus affected by the gravity of everything behind it, we would expect this explosion to slow down after a while.

It doesn’t. In fact, the expansion of our universe is actually getting faster over time, which is as crazy as if you threw a baseball that kept getting faster and faster instead of falling back to the ground (though don’t try that at home). This means, in effect, that space is always growing. The only way to explain this is with dark matter, or, more accurately, dark energy, which is the driving force behind this cosmic acceleration. So what in the world is dark energy, you ask? Well, that’s another interesting thing…

5

All Matter is Just Energy

It’s true—matter and energy are just two sides of the same coin. In fact, you’ve known this your whole life, if you’ve ever heard of the formula E = mc^2. The E is for energy, and the m represents mass. The amount of energy contained in a particular amount of mass is determined by the conversion factor c squared, where c represents—wait for it—the speed of light.

The explanation for this phenomenon is really quite fascinating, and it has to do with the fact that the mass of an object increases as it approaches the speed of light (even as time is slowing down). It is, however, quite complicated, so for the purposes of this article, I’ll simply assure you that it’s true. For proof (unfortunately), look no further than atomic bombs, which convert very small amounts of matter into very large amounts of energy.

Speaking of things that are other things…

At first glance, particles (such as an electron) and waves (such as light) couldn’t be more different. One is a solid chunk of matter, and the other is a radiating beam of energy, kind of. It’s apples and oranges. But as it turns out, things like light and electrons can’t really be confined to one state of existence—they act as both particles and waves, depending on who’s looking.

No, seriously. I know that sounds ridiculous (and it’ll sound even crazier when we get to Number 1), but there’s concrete evidence that proves light is a wave, and other concrete evidence that proves light is a particle (ditto for electrons). It’s just… both. At the same time. Not some sort of intermediary state between the two, mind you—physically both, in the sense that it can be either. Don’t worry if that doesn’t make a lot of sense, because we’re back in the realm of quantum mechanics, and at that level, the universe doesn’t like to be made sense of anyway.

3

All Objects Fall at the Same Speed

Let’s calm things down for a second, because modern physics is a lot to take in at once. That’s okay—classical physics proved some pretty cool concepts too.

You would be forgiven for assuming that heavier objects fall faster than lighter ones—it sounds like common sense, and besides, you know for a fact that a bowling ball drops more quickly than a feather. And this is true, but it has nothing to do with gravity—the only reason this occurs is because the earth’s atmosphere provides resistance. In reality, as Galileo first realized about 400 years ago, gravity works the same on all objects, regardless of their mass. What this means is that if you repeated the feather/bowling ball experiment on the moon (which has no atmosphere), they would hit the ground at the exact same time.

Alright, break over. Things are going to get weird again.

The thing about empty space, you’d think, is that it’s empty. That sounds like a pretty safe assumption—it’s in the name, after all. But the universe, it happens, is too restless to put up with that, which is why particles are constantly popping into and out of existence all over the place. They’re called virtual particles, but make no mistake—they’re real, and proven. They exist for only a fraction of a second, which is long enough to break some fundamental laws of physics but quick enough that this doesn’t actually matter (like if you stole something from a store, but put it back on the shelf half a second later). Scientists have called this phenomenon ‘quantum foam,’ because apparently it reminded them of the shifting bubbles in the head of a soft drink.

1

The Double Slit Experiment

So remember a few entries ago, when I said everything was both a wave and a particle at the same time? Of course you do, you’ve been following along meticulously. But here’s the other thing—you know from experience that things have definite forms—an apple in your hand is an apple, not some weird apple-wave thing. So what, then, causes something to definitively become a particle or a wave? As it turns out, we do.

The double slit experiment is the most insane thing you’ll read about all day, and it works like this—scientists set up a screen with two slits in front of a wall, and shot a beam of light through the slits so they could see where it hit on the wall. Traditionally, with light being a wave, it would exhibit something called a diffraction pattern, and you would see a band of light spread across the wall. That’s the default—if you set up the experiment right now, that’s what you would see.

But that’s not how particles would react to a double slit—they would just go straight through to create two lines on the wall that match up with the slits. And if light is a particle, why doesn’t it exhibit this property instead of a diffraction pattern? The answer is that it does—but only if we want it to. See, as a wave, light travels through both slits at the same time, but as a particle, it can only travel through one. So if we want it to act like a particle, all we have to do is set up a tool to measure exactly which slit each bit of light (called a photon) goes through. Think of it like a camera—if it takes a picture of each photon as it passes through a single slit, then that photon can’t have passed through both slits, and thus it can’t be a wave. As a result, the interference pattern on the wall won’t appear—the two lines will instead. Light will have acted as a particle merely because we put a camera in front of it. We physically change the outcome just by measuring it.

It’s called the Observer Effect, generally speaking, and though it’s a good way to end this article, it doesn’t even scratch the surface of crazy things to be found in physics. For example, there are a bunch of variations of the double slit experiment that are even more insane than the one I talked about here. I encourage you to look them up, but only if you’re prepared to spend the whole day getting caught up in quantum mechanics.